By Terry Deem-Reilly, CSU Extension – Denver Master Gardener since 2003

A LITTLE BACKGROUND ON THE SUBJECT

The question of whether certain gardening practices help or harm the natural world has become a major consideration in recent years. Consequently, gardeners have adopted strategies to support our ecosystem, especially by including native and adapted plants to foster genetic diversity and the flourishing of local mammals, birds, and insects. These creatures, having evolved alongside our native plants, are attracted to natives for food and protection, while spreading the pollen necessary for the plants’ seed production and propagation.

Gardeners’ enthusiasm for the use of natives has sparked the production and sale of this class of plants through catalogs and nurseries and its promotion in gardening literature. Where once only new varieties of old standards were garden possibilities, we now have expanding availability of natives. Add the general concern about climate change and sustainability to the mix, and we’re pretty much sold on this class of plants!

When a new class of sexy plants bursts upon the market, the demand is ever-increasing and intense. There also aren’t enough true natives in a sufficient variety to fulfill our cravings for unusual colors, sizes, foliage, and blooms. Given this, huge numbers of native plant cultivars – known as “nativars” – have emerged to fill the gap. This seems like a textbook operation of market forces, except for one thing: the effects of planting nativars on our cherished natives and, by extension, on the entire ecosystem are big, big unknowns.

LET’S DEFINE SOME TERMS

Before getting into the tall grass on this question, we’ll add some definitions:

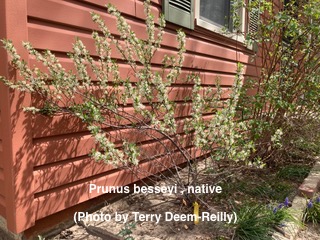

- “Native” refers to a plant that was growing in the Americas before widespread European settlement, which began about 200 years ago.

- “Cultivar” designates a plant selected and bred for certain traits that is (usually) propagated by cloning. Many are the results of crossbreeding between species and (sometimes) genera.

- A “nativar” is a cultivar of a native plant that often produces sterile flowers (and therefore won’t reseed itself). It’s usually identified by genus, species, and a cultivar name in quotes, e.g. Physocarpus opulifolius ‘Red Robe,’ as opposed to the native ninebark, known as just plain Physocarpus opulifolius.

A FEW THINGS TO THINK ABOUT

Natives have been growing and evolving alongside their pollinators and other wildlife without human intervention for millennia; plants, animals, and insects have formed a nice symbiosis that supplies all involved with sufficient food, shelter, and opportunities to reproduce. But now humans are introducing new factors into ancient relationships that may affect our ecosystems in unknown ways for a long period of time. Gardeners should therefore think carefully about the desirability of introducing nativars created by unnatural means into a natural environment.

Popular horticultural literature and educational programs haven’t addressed this issue, but organizations devoted to best horticultural knowledge and practices have compiled science-based publications (including extensive reference lists) that shed a great deal of light on the pros and cons of using nativars in home gardens.

Let’s examine seven misperceptions about nativars, courtesy of the Maryland Cooperative Extension:

- It’s always bad to use nativars. Nope. Sterile nativars (look for blossoms that lack stamens) aren’t harmful, and some nativars are being bred for disease and pest-resistant features.

- The number of plants in cultivated gardens is outnumbered by natives in the wild. Numbers don’t necessarily translate into impact. And wild areas often occupy much less land than developed areas.

- Urban nativars can’t interbreed with natives in natural areas. Wind-borne pollen can travel a long way, and some pollinators are migratory.

- Adding nativar genes into native populations increases genetic diversity. This might be true if diversity is adaptive, not random (as with plants introduced by humans). And a nativar bred for higher vigor can compete with natives to the detriment of the latter.

- Plants’ performance is best measured by how often they’re visited by pollinators. Disruption of the natural balance cancels out perceived advantages of increased visits.

- Nativars created by spontaneous mutations (“sports”) don’t affect the ecosystem. Sports can be produced by recessive genes resulting from inbreeding, and random mutations lack the adaptability characteristic of native plants.

RESOURCES

CSU Extension takes no position pro or con concerning nativars, but I’m offering some helpful online resources below for further research. And of course, Denver County Extension stands ready to assist with information about this and any other horticultural concern!

Native vs. “nativar” – do cultivars of native plants have the same benefits?

A Guide to Native Plants: Straight Species vs. Nativars

The Nativar Conundrum: New Research on Natives vs. Native Cultivars with Dr. Doug Tallamy

REFERENCES

Cultivars of Native Plants | University of Maryland Extension. (n.d.). Extension.umd.edu. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/cultivars-native-plants/

Keeping Nature Near. (n.d.). Grow Native! https://grownative.org